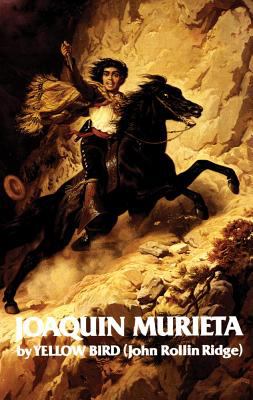

The Sonoran outlaw, Joaquin Murieta is one of those historical figures who was a real person but whose factual existence has been so clouded by myth that now he’s more literary than historical. Of course, this isn’t much of a problem for us in the world of literature. After all, even historical figures have a literary equivalent, a version of themselves that signify some greater, larger abstract ideas. Sure, there might be a historical Lincoln, but that doesn’t mean we can’t also have our own badass, vampire-killin’ version of Honest Abe as well. Interesting enough, it was the Native American author, John Rollin Ridge, who wrote the ur-text of the Murieta mythos, The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit, which also happens to be the first novel written by a Native American.

The Sonoran outlaw, Joaquin Murieta is one of those historical figures who was a real person but whose factual existence has been so clouded by myth that now he’s more literary than historical. Of course, this isn’t much of a problem for us in the world of literature. After all, even historical figures have a literary equivalent, a version of themselves that signify some greater, larger abstract ideas. Sure, there might be a historical Lincoln, but that doesn’t mean we can’t also have our own badass, vampire-killin’ version of Honest Abe as well. Interesting enough, it was the Native American author, John Rollin Ridge, who wrote the ur-text of the Murieta mythos, The Life and Adventures of Joaquin Murieta: The Celebrated California Bandit, which also happens to be the first novel written by a Native American.

Ridge (whose Cherokee name was Yellow Bird) lived an interesting life, almost interesting enough to compete with his most famous literary work. Ridge was the son of John Ridge and grandson of Major Ridge, leaders of a group of Cherokee who, prior to the forced removal from Cherokee lands, struck a deal with the U.S. government, known as the Treaty of New Echota, that would cede Cherokee lands in exchange for compensation. Understandably, this was an unpopular position among the Cherokee, but you can see the logic behind the Treaty Party’s position. They felt that removal was inevitable, so they wanted to strike the best deal possible.

Many other Cherokee saw these actions as a betrayal, and after enduring the Trail of Tears and removal to Indian Territory in the West, many of the leaders of the Treaty Party were assassinated, including Ridge’s father and grandfather, John Ridge and Major Ridge.

Ridge eventually made his way to California during the gold rush, but unsatisfied with mining turned towards writing as his trade, eventually writing a highly fictionalized version of the exploits of Joaquin Murieta. Joaquin Murieta: The Novel is a fascinating, contradictory, and often shockingly violent story. Throughout, however, it’s infused with real feelings of love, anger, and betrayal. Arguably, the object of love and hate is the United States herself.

Early on, Ridge establishes that the story of Murieta is not singular; it’s the story of circumstances:

The character of this truly wonderful man was nothing more than a natural production of the social and moral condition in which he lived, acting upon certain peculiar circumstances favorable to such a result, and, consequently, his individual history is part of the most valuable history of the State. (7)

Here and elsewhere you can feel Ridge working out his complex feelings about the nation on the page. Murieta is a dashing outlaw, a good man turned to do bad things, a victim of circumstances.

In their heyday, the Ridge family were wealthy Cherokee elites who held positions of power and esteem. The Cherokee themselves were a part of the five civilized tribes, which meant they adopted a number of white customs, in part strategically assimilating as a means to protect their rights from white settlers. In fact, the Ridges even owned slaves. If things had gone differently, if his family hadn’t signed the Treaty of New Echota, then he too may have become an important leader among the Cherokee people. In part, the Ridges achieved their positions of prominence because they were able to deftly navigate both white and native worlds, acculturating when it was advantageous.

power and esteem. The Cherokee themselves were a part of the five civilized tribes, which meant they adopted a number of white customs, in part strategically assimilating as a means to protect their rights from white settlers. In fact, the Ridges even owned slaves. If things had gone differently, if his family hadn’t signed the Treaty of New Echota, then he too may have become an important leader among the Cherokee people. In part, the Ridges achieved their positions of prominence because they were able to deftly navigate both white and native worlds, acculturating when it was advantageous.

It’s not hard to see a bit of Ridge in Murieta as he immigrated to California “fired with enthusiastic admiration of the American character” (8). But this enthusiasm is soon dashed. After much initial success in mining, Americans jealous of his success violently beat him, tie him up, and then rape his wife in front of him. Murieta continues to mine for gold, chasing his initial success, only to be attacked by Americans once again. (Usually, these sorts of tales only require one violent inciting incident, but Ridge has Murieta victimized a second time). This time whites accuse him of being a horse thief, tie him up and whip him, and then go to his half-brother’s house and hang him.

Naturally, after enduring this sort of violence, Murieta forms a band of robbers. California during the gold rush was a multicultural place, and whites established laws that prevented non-whites from competing in the gold mining craze, including the 1850 Foreign Miners’ Tax Law, which had the intent of making it nearly impossible for people of color to compete with whites in the gold rush by establishing a cumbersome bureaucracy and taxes that applied only to “foreigners.”

Despite the violence he endured, Murieta is the consummate gentleman thief. He occasionally prefers to let people go rather than murder them, and when his enemies get the best of him, he often laughs it off. When Murieta and his men are betrayed by seemingly friendly Tejon Indians, he eventually “burst out into a loud laugh at his ridiculous position, and ever afterwards endured his captivity with a quiet smile” (38).

Interesting enough, during Murieta’s time as the captive of the Tejon Indians, Ridge paints a largely unflattering portrait the Tejon people. Although, they are some of the few people who can win one over on Murieta, they’re also described as “poor,” “miserable,” and “cowardly.” Presumably, as a partially acculturated member of one of the “civilized” tribes, Ridge sees himself and the Cherokee in general as superior to the Tejon. His somewhat unkind portrayal of California Indians may also be a way for him to distance himself from “those Indians.”

Ridge seems unable to fully identify with California Native Americans, but this isn’t the only strange, tangled relationship the novel has with race. While Murieta can take a joke and lose a few battles without losing his sense of humor, his chief lieutenant, Three Finger Jack can’t. In fact, he’s shockingly bloodthirsty, especially when it comes to killing Chinese: “ ‘Well,’ said Jack, ‘I can’t help it; but, somehow or other, I love to smell the blood of a Chinaman. Besides, it’s such easy work to kill them. It’s a kind of luxury to cut their throats’” (64). And here is the crux of Joaquin Murieta’s weird relationship with race: Murieta is both a victim of racialized violence while his gang is simultaneously a perpetrator of racialized violence.

If we were to map Ridge’s psyche onto his text, then surely Three Finger Jack would be the id to Murieta’s ego. The astute gentleman thief of Murieta surely represents how Ridge, an educated man descended from a once powerful family, sees himself. But within Three Finger Jack, Ridge can arguably release his unfettered rage, lashing out at white racists and Chinese settlers alike.

Even though Ridge is the first Native American to write a novel, like many nineteenth-century authors, he doesn’t fit nicely into our modern conception of how a minority author is supposed to tackle issues of race and colonialism. We don’t expect denunciations of white colonial racism to sit side by side with leering depictions of violence against immigrants, which is one of the reasons why the text is so valuable as an object of study and analysis. Not all minority authors could be as incredibly ahead of their time as Frederick Douglass.

Of course, as a son of slave owners, we of course shouldn’t expect racial solidarity from Ridge. But Joaquin Murieta’s anger at injustice and simultaneous rage against innocents reminds me a lot of the cult films of the 70s and 80s, like Repo Man, They Live, A Boy and His Dog, Death Race 2000, and Escape from New York. These are explicitly political films that pummel their targets of with anger and a good bit of irony. Arguably, the politics in these films are mostly liberal, but there’s a not-so-hidden mean streak that runs through all of them. The raw anger of these cult classics is also what drew me to them in my youth, and if I’m being honest, one of the reasons why I return to many of them now that I’m older.

But like Joaquin Murieta, the target of these movie’s anger often slips, often landing not on Reaganomics or inequality but on women. LIke Ridge’s casual violence towards the Chinese and semi-dismissive portrayal of California Native Americans, misogyny is an unfortunate byproduct of so many cult classics of the late twentieth century. If I would draw a hasty framework connecting a novel from the 1840s and movies from the 1970s and 80s, then I might claim that anger at injustice done to us by society can so easily curdle into anger at other, easier targets. It’s not so difficult to both punch up and down at the same time. Looking at the world around us, where anger is hardly in short supply, this seems like a useful reminder.

And that’s what we got with Ben Garrison’s cartoon, “The Siren Song of Socialism,” which was passed around the internet by both conservatives as a stern warning against the evils of socialism and by liberals as an example of how far off the deep end the right has fallen. If you haven’t seen it, the cartoon consists of a man dressed in a flannel and blue jeans tied, like Odysseus, to the mast under which Garrison has helpfully included the label “millennials.” The man is excitedly leering at three women on an island representing Kamala Harris, Tulsi Gabbard, and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, each scantily-clad in “island” garb. At the head of the ship, a stern Trump informs the man, “We’re not going there!”

And that’s what we got with Ben Garrison’s cartoon, “The Siren Song of Socialism,” which was passed around the internet by both conservatives as a stern warning against the evils of socialism and by liberals as an example of how far off the deep end the right has fallen. If you haven’t seen it, the cartoon consists of a man dressed in a flannel and blue jeans tied, like Odysseus, to the mast under which Garrison has helpfully included the label “millennials.” The man is excitedly leering at three women on an island representing Kamala Harris, Tulsi Gabbard, and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, each scantily-clad in “island” garb. At the head of the ship, a stern Trump informs the man, “We’re not going there!” Once they had finally killed the whale, the whalers must drag the massive carcass to the ship where they must peel away and process the blubber. The dead whale was fastened to the starboard side of the ship where planks were erected for the whalers to cut off strips of blubber, like they were peeling an apple. The blubber was then boiled and eventually stored in barrels. The crew and ship would become stained by oil and blood, and the massive carcass could become a beacon for nearby sharks, which was just another danger whalers faced if they happened to slide off the now slippery deck. The stench of the processing whale blubber into oil would have been overwhelming, Melville describing it as smelling “like the left wing of the day of judgment” (475).

Once they had finally killed the whale, the whalers must drag the massive carcass to the ship where they must peel away and process the blubber. The dead whale was fastened to the starboard side of the ship where planks were erected for the whalers to cut off strips of blubber, like they were peeling an apple. The blubber was then boiled and eventually stored in barrels. The crew and ship would become stained by oil and blood, and the massive carcass could become a beacon for nearby sharks, which was just another danger whalers faced if they happened to slide off the now slippery deck. The stench of the processing whale blubber into oil would have been overwhelming, Melville describing it as smelling “like the left wing of the day of judgment” (475). Of course, as a man of the nineteenth century, Melville also brought plenty of baggage with him. His account of the Typee isn’t without some of the racist assumptions of the day, even if it was more progressive than many peers. And both Garrison and Melville view everything through the male gaze. Freedom for Melville also means free access to women’s bodies, and parts of Typee were censored because they featured between the sailors and the Polynesian women.

Of course, as a man of the nineteenth century, Melville also brought plenty of baggage with him. His account of the Typee isn’t without some of the racist assumptions of the day, even if it was more progressive than many peers. And both Garrison and Melville view everything through the male gaze. Freedom for Melville also means free access to women’s bodies, and parts of Typee were censored because they featured between the sailors and the Polynesian women.  Everyone knows about that time Tom Sawyer tricked the neighborhood kids into painting his aunt’s fence for him. Everyone knows about his time hiding out on Jackson Island with his friend Huck Finn and when he made his way out of McDougal’s Cave with his swe

Everyone knows about that time Tom Sawyer tricked the neighborhood kids into painting his aunt’s fence for him. Everyone knows about his time hiding out on Jackson Island with his friend Huck Finn and when he made his way out of McDougal’s Cave with his swe

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn ned with many of the same stereotypes associated with the poor in America. He’s lazy, he’s a drunk, and he’s an unrepentant racist. In

ned with many of the same stereotypes associated with the poor in America. He’s lazy, he’s a drunk, and he’s an unrepentant racist. In  When I was ten, Tom Sawyer tricked me. Not only did he convince me to paint his aunt’s fence, a chore he was supposed to complete on his own, but he somehow got me to give him a big glass stopper and a tin soldier for the honor. I never forgave him.

When I was ten, Tom Sawyer tricked me. Not only did he convince me to paint his aunt’s fence, a chore he was supposed to complete on his own, but he somehow got me to give him a big glass stopper and a tin soldier for the honor. I never forgave him. ent who has had a more tumultuous

ent who has had a more tumultuous  he estimates to have average twelve miles an hour, Grant claims the conveyances “seemed like annihilating space.” Prior to the Civil War space is annexed and annihilated. (It’s no coincidence that Grant uses the language of violence for the speed and reach of the railroad).

he estimates to have average twelve miles an hour, Grant claims the conveyances “seemed like annihilating space.” Prior to the Civil War space is annexed and annihilated. (It’s no coincidence that Grant uses the language of violence for the speed and reach of the railroad). ere rereleased a few years ago. But Grant himself is another story. After a century, the lost cause narrative of the Civil War is finally losing its grip on our understanding of the nineteenth-century. Played by Jared Harris, Grant was even given a badass introduction by Steven Spielberg in

ere rereleased a few years ago. But Grant himself is another story. After a century, the lost cause narrative of the Civil War is finally losing its grip on our understanding of the nineteenth-century. Played by Jared Harris, Grant was even given a badass introduction by Steven Spielberg in  In 1948,

In 1948,  Robert W. Chambers has become an apparition in American literature. He’s barely read anymore, but we can feel his ghostly presence across dimensions, mostly through his influence on writers like H.P. Lovecraft whose popularity has only increased in recent years thanks to the

Robert W. Chambers has become an apparition in American literature. He’s barely read anymore, but we can feel his ghostly presence across dimensions, mostly through his influence on writers like H.P. Lovecraft whose popularity has only increased in recent years thanks to the  It’s not often that a densely researched academic text enters the national conversation. Often there’s a thick barrier between academic and public discourse. The only means to break through this divide is to funnel research that’s important to the public into a more easily digestible op-ed. But the idea that an economist could get the general public to run out and purchase a 600-plus page tome that pores through centuries of data on income inequality seems especially improbable in our day and age of bit-sized digital text and information. Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, whose English translation came out in 2014, is that 600-plus page tome. And while Piketty’s centuries spanning analysis of income inequality isn’t exactly a beach read, it’s also clear that Piketty believes his work is important enough for a non-academic audience and clearly wrote his study so that it could be read by anyone willing to put in a little elbow grease.

It’s not often that a densely researched academic text enters the national conversation. Often there’s a thick barrier between academic and public discourse. The only means to break through this divide is to funnel research that’s important to the public into a more easily digestible op-ed. But the idea that an economist could get the general public to run out and purchase a 600-plus page tome that pores through centuries of data on income inequality seems especially improbable in our day and age of bit-sized digital text and information. Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century, whose English translation came out in 2014, is that 600-plus page tome. And while Piketty’s centuries spanning analysis of income inequality isn’t exactly a beach read, it’s also clear that Piketty believes his work is important enough for a non-academic audience and clearly wrote his study so that it could be read by anyone willing to put in a little elbow grease. The first episode of the TV show

The first episode of the TV show