Last year a viral Tweet collecting screenshots of Gen Z Tik-Tok denizens mocking Millennials went viral. Millennials like myself may have been taken aback because, even though many of us are now in our mid to late thirties, we’ve had to read at least fifteen years worth of articles about the various businesses we’re destroying by not making enough money to be comfortably middle class. Gen Z made fun of us for liking Harry Potter and using the word “adulting” (both accusations accurate and fair). But tucked into the list of things to make fun of Millennials for was talking about “tech start-ups.”

I couldn’t help but think about Gen Z mocking the Millennial obsession with tech start-ups while reading Anna Wiener’s memoir, Uncanny Valley. What was once our generation’s gold rush, a respectable way to get rich and “change the world” for the better has now become passe, almost embarrassing. As a recent graduate, Wiener wanted to work in publishing, but found herself stuck in the role of personal assistant scraping enough to barely survive in New York City. While those firmly established in the industry see this sort of precarity as simply paying your dues, any millennial would recognize it for what it is: exploitation. Wiener decided to ditch her moribound industry for a New York e-reading startup, which eventually led to a move to San Francisco.

Throughout the memoir, Wiener uses a technique where she references companies but does not name them. Proper nouns are translated into phrases. For instance, Facebook becomes “the social network everybody hates.” It’s a clever way to lightly anonymize the companies she worked for, and perhaps generalize her experiences. (Of course, it’s likely also a way to avoid any NDAs she may have had to sign). But it doesn’t take much work to discover that the two companies Wiener worked for were Mixpanel and Github.

Wiener’s memoir is largely outward facing. We don’t learn too much about her outside of her work life, which I think works to the story’s advantage by allowing the narrative to tightly focus on Silicon Valley. I found her to present a rather even-handed analysis of startup culture, perhaps even giving too many tech bros the benefit of the doubt. There’s a fine line between open-minded and naive.

She’s careful not to present individuals as caricatures. A rising CEO might have a libertarian streak, but he’s also interested in prison abolition. The aloof, but brilliant programmer at the data analytics company enjoys making artistic, non-commercial games in his free time. With any system, it’s not the individuals who are the problem. If everyone in Silicon Valley all of a sudden became well intentioned do-gooders, then it wouldn’t solve the problems of misinformation, privacy violations, and gentrification these companies have caused.

But Wiener also confirms a number of stereotypes about Silicon Valley culture. It’s true that startups are mostly run and staffed by male twenty-somethings. There’s a cult-like nature to these workplaces where instead of suits, employees sport t-shirts and other garb blazoned with the name of the company. There’s an ideological obsession with efficiency that extends to viewing the body as just another system to be “hacked.” The Silicon Valley boom has led to the gentrification of San Francisco, exacerbating its housing crises and contributing to the excess of pretentious restaurants and bars, like one where you tell the “mixologist” three adjectives instead of just ordering a drink. Also, people listen to, ugh, EDM. (Whatever happened to EDM?)

As a woman in a male dominated industry, Wiener had to endure a general miasma of sexism, including resistance by some colleagues to diversifying the tech industry as well as overt harassment. While sharing a cab, a coworker put his hand under her blouse and then down her skirt. Another employee casually mentions to her how much he loves dating Jewish women because they’re so sensual. She mentions the latter incident to her boss, but he does nothing. And while these incidents seem bad enough, Wiener notes that what happened to her pales compared to what many other women in tech went through.

The larger problem with Silicon Valley, however, is structural and ideological. VC firms pump billions of dollars into companies that, despite the rosy image they project, too often make the world worse. Google may have adopted the slogan “Don’t be evil,” but Facebook’s mantra, “Move fast and break things” is likely a more accurate description of how tech companies operate.

There’s a strong undercurrent of techno-utopia libertarianism that pervades Silicon Valley culture. People in tech laud the idea of special economic zones while ignoring the brutal working conditions and child labor they produce. They promote patriarchal and racist hierarchies under the guise of “just asking questions.” And they seem perpetually unaware of historical and cultural context. As Wiener notes, all the new and exciting political ideas Silicon Valley comes up with are just old ideas that we’ve moved past, and for a good reason. They’re recycling late 19th-century Gilded Age ideology, but are too ignorant of history to even recognize it.

The one question that Wiener struggles with and doesn’t satisfactorily answer is whether people of Silicon Valley actually believe their techno-optimist line or whether these are just empty slogans. It’s something I’ve wondered about myself. Facebook presents itself as a company that brings people together, but it actually spreads misinformation and gives safe harbor to white supremacists. Uber has billed itself as a company that will revolutionize transportation, lead to less car ownership and help the environment. Instead it has ruined the lives of many immigrant taxi drivers and spread more CO2 into the atmosphere. Do the CEOs of these companies really think they’re making the world a better place?

This is an especially pertinent question when it comes to SIlicon Valley because these companies received so much free uncritical press coverage for so long. Hell, the media was ready to credit Twitter with the 2011 Egyptian Revolution as if protests never happened before the existence of the micro-blogging site. Silicon Valley branded itself with the old adage that you can “Do well while doing good.” Plenty of people were snookered, but I’ve always wondered whether that included the startups themselves. Were they naive enough to believe their own utopian hype machine? Ultimately, I see Uncanny Valley as a memoir about meaning and work. Wiener was unhappy in publishing because there was no way forward, but she still found meaning in writing and literature. Working in tech, however, gives her a sense of accomplishment and a paycheck that allows her to live in one of the most expensive cities in the U.S., but eventually she begins to doubt whether the good of these companies outweigh the harm they’re doing. As a motivational tool, a paycheck only takes you so far. You’re not going to get people to give over their lives to a company if it’s a simple exchange of labor for coin. And I have a sneaking suspicion that this is true of the rank and file as much as it’s true of the ownership class. You can accumulate as much as possible in life, but when all is said and done, what have you actually accomplished with your time here on Earth? And even worse, when you’re on the cutting edge, you’re still no more than a decade away from becoming passe. What happens when the youngins no longer think you’re cool?

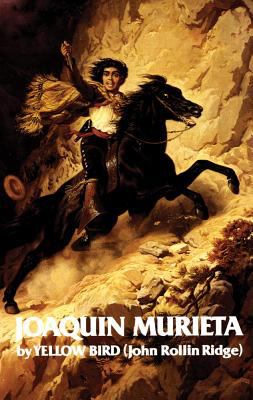

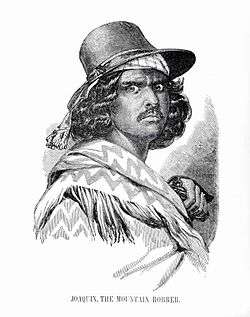

The Sonoran outlaw, Joaquin Murieta is one of those historical figures who was a real person but whose factual existence has been so clouded by myth that now he’s more literary than historical. Of course, this isn’t much of a problem for us in the world of literature. After all, even historical figures have a literary equivalent, a version of themselves that signify some greater, larger abstract ideas. Sure, there might be a historical Lincoln, but that doesn’t mean we can’t also have our own badass, vampire-killin’ version of Honest Abe as well. Interesting enough, it was the Native American author,

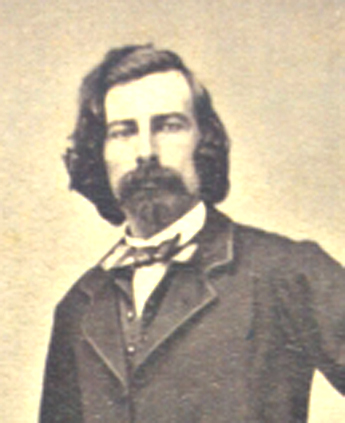

The Sonoran outlaw, Joaquin Murieta is one of those historical figures who was a real person but whose factual existence has been so clouded by myth that now he’s more literary than historical. Of course, this isn’t much of a problem for us in the world of literature. After all, even historical figures have a literary equivalent, a version of themselves that signify some greater, larger abstract ideas. Sure, there might be a historical Lincoln, but that doesn’t mean we can’t also have our own badass, vampire-killin’ version of Honest Abe as well. Interesting enough, it was the Native American author,  power and esteem. The Cherokee themselves were a part of the five civilized tribes, which meant they adopted a number of white customs, in part strategically assimilating as a means to protect their rights from white settlers. In fact, the Ridges even owned slaves. If things had gone differently, if his family hadn’t signed the Treaty of New Echota, then he too may have become an important leader among the Cherokee people. In part, the Ridges achieved their positions of prominence because they were able to deftly navigate both white and native worlds, acculturating when it was advantageous.

power and esteem. The Cherokee themselves were a part of the five civilized tribes, which meant they adopted a number of white customs, in part strategically assimilating as a means to protect their rights from white settlers. In fact, the Ridges even owned slaves. If things had gone differently, if his family hadn’t signed the Treaty of New Echota, then he too may have become an important leader among the Cherokee people. In part, the Ridges achieved their positions of prominence because they were able to deftly navigate both white and native worlds, acculturating when it was advantageous.

And that’s what we got with Ben Garrison’s cartoon, “The Siren Song of Socialism,” which was passed around the internet by both conservatives as a stern warning against the evils of socialism and by liberals as an example of how far off the deep end the right has fallen. If you haven’t seen it, the cartoon consists of a man dressed in a flannel and blue jeans tied, like Odysseus, to the mast under which Garrison has helpfully included the label “millennials.” The man is excitedly leering at three women on an island representing Kamala Harris, Tulsi Gabbard, and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, each scantily-clad in “island” garb. At the head of the ship, a stern Trump informs the man, “We’re not going there!”

And that’s what we got with Ben Garrison’s cartoon, “The Siren Song of Socialism,” which was passed around the internet by both conservatives as a stern warning against the evils of socialism and by liberals as an example of how far off the deep end the right has fallen. If you haven’t seen it, the cartoon consists of a man dressed in a flannel and blue jeans tied, like Odysseus, to the mast under which Garrison has helpfully included the label “millennials.” The man is excitedly leering at three women on an island representing Kamala Harris, Tulsi Gabbard, and Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, each scantily-clad in “island” garb. At the head of the ship, a stern Trump informs the man, “We’re not going there!” Once they had finally killed the whale, the whalers must drag the massive carcass to the ship where they must peel away and process the blubber. The dead whale was fastened to the starboard side of the ship where planks were erected for the whalers to cut off strips of blubber, like they were peeling an apple. The blubber was then boiled and eventually stored in barrels. The crew and ship would become stained by oil and blood, and the massive carcass could become a beacon for nearby sharks, which was just another danger whalers faced if they happened to slide off the now slippery deck. The stench of the processing whale blubber into oil would have been overwhelming, Melville describing it as smelling “like the left wing of the day of judgment” (475).

Once they had finally killed the whale, the whalers must drag the massive carcass to the ship where they must peel away and process the blubber. The dead whale was fastened to the starboard side of the ship where planks were erected for the whalers to cut off strips of blubber, like they were peeling an apple. The blubber was then boiled and eventually stored in barrels. The crew and ship would become stained by oil and blood, and the massive carcass could become a beacon for nearby sharks, which was just another danger whalers faced if they happened to slide off the now slippery deck. The stench of the processing whale blubber into oil would have been overwhelming, Melville describing it as smelling “like the left wing of the day of judgment” (475). Of course, as a man of the nineteenth century, Melville also brought plenty of baggage with him. His account of the Typee isn’t without some of the racist assumptions of the day, even if it was more progressive than many peers. And both Garrison and Melville view everything through the male gaze. Freedom for Melville also means free access to women’s bodies, and parts of Typee were censored because they featured between the sailors and the Polynesian women.

Of course, as a man of the nineteenth century, Melville also brought plenty of baggage with him. His account of the Typee isn’t without some of the racist assumptions of the day, even if it was more progressive than many peers. And both Garrison and Melville view everything through the male gaze. Freedom for Melville also means free access to women’s bodies, and parts of Typee were censored because they featured between the sailors and the Polynesian women.  Everyone knows about that time Tom Sawyer tricked the neighborhood kids into painting his aunt’s fence for him. Everyone knows about his time hiding out on Jackson Island with his friend Huck Finn and when he made his way out of McDougal’s Cave with his swe

Everyone knows about that time Tom Sawyer tricked the neighborhood kids into painting his aunt’s fence for him. Everyone knows about his time hiding out on Jackson Island with his friend Huck Finn and when he made his way out of McDougal’s Cave with his swe

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn ned with many of the same stereotypes associated with the poor in America. He’s lazy, he’s a drunk, and he’s an unrepentant racist. In

ned with many of the same stereotypes associated with the poor in America. He’s lazy, he’s a drunk, and he’s an unrepentant racist. In

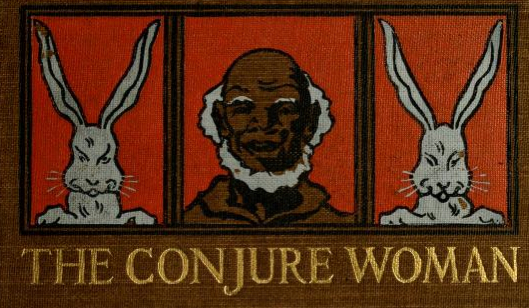

In the classroom, I’m certain that photographs of Charles Chestnutt have been taught at least as often as his writing. Although he identified as black, Chestnutt could have passed as white, and at different points in his lifetime in different states he would have been legally deemed white or black. Chestnutt becomes a readily available example of the legal and cultural construction of race.

In the classroom, I’m certain that photographs of Charles Chestnutt have been taught at least as often as his writing. Although he identified as black, Chestnutt could have passed as white, and at different points in his lifetime in different states he would have been legally deemed white or black. Chestnutt becomes a readily available example of the legal and cultural construction of race.

When I was ten, Tom Sawyer tricked me. Not only did he convince me to paint his aunt’s fence, a chore he was supposed to complete on his own, but he somehow got me to give him a big glass stopper and a tin soldier for the honor. I never forgave him.

When I was ten, Tom Sawyer tricked me. Not only did he convince me to paint his aunt’s fence, a chore he was supposed to complete on his own, but he somehow got me to give him a big glass stopper and a tin soldier for the honor. I never forgave him.