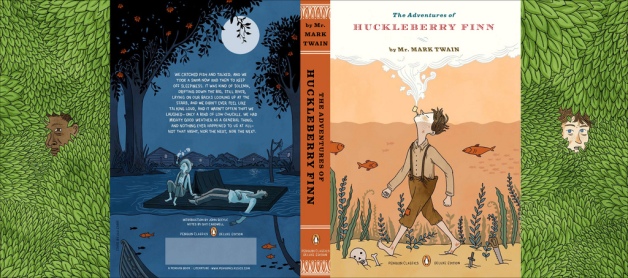

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn might be the most laid-back of any “Great American Novel.” It goes down as easy as iced tea on a summer day or a dry stout after a long day of work. Let’s just take a moment to appreciate the cover of Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition (the copy I own) by Lilli Carre. Just look at how delightful that image is. Doesn’t it just invite you to take an adventure on the mighty Mississippi? And doesn’t it promise that the adventure will be fun, even exciting, but that in the end, no one will get hurt?

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn might be the most laid-back of any “Great American Novel.” It goes down as easy as iced tea on a summer day or a dry stout after a long day of work. Let’s just take a moment to appreciate the cover of Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition (the copy I own) by Lilli Carre. Just look at how delightful that image is. Doesn’t it just invite you to take an adventure on the mighty Mississippi? And doesn’t it promise that the adventure will be fun, even exciting, but that in the end, no one will get hurt?

That’s not exactly true of the story itself. A few people die, including Huck’s drunken and abusive dad (who we’ll get to in a bit), but the story is so wrapped up in irony that when Huck once again teams up with Tom Sawyer in the final act in order to rescue the escaped slave Jim, Tom purposefully creates obstacles for the rescue so that it better resembles the adventure novels he’s read.

I mean, take a look at the inscription that opens the novel:

NOTICE.

Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.

BY ORDER OF THE AUTHOR

Per G. G. Chief of Ordinance

It almost makes it possible to not read anything into the novel, to refuse to peak under the veil, to plumb the subtext, and to just come along for the adventure.

But we can’t. No, it’s just not in our constitution. So when rereading Huck Finn after about a decade, I couldn’t help but draw connections between the world Twain crafted and our own. (By the by, G. G. in the above inscription likely refers to General Grant who Twain befriended. Twain even published Grant’s memoir.) Huck Finn draws a picture of a fragmented, inchoate nation. Its very geography speaks to differing, contested, and overlapping peoples, governments, customs, borders, and languages. The narrative spans the length of the Mississippi, a commercial byway that seems to be the only link to disparate, isolated communities. In other words, the world of Huck Finn is startling familiar to the United States of today.

Before we even get started on Huck’s trip down the Mississippi, Twain highlights the divided nature of America as embodied in speech:

In this book a number of dialects are used, to wit: the Missouri negro dialect; the extremest form of the backwoods South-Western dialect; the ordinary “Pike-County” Dialect; and the modified varieties of this last…I make this explanation for the reason that without it many readers would suppose that all these characters were trying to talk alike and not succeeding.

Through multiple dialects, Twain illustrates ways in which we barely speak the same language, and in fact language serves as much a means of division as a means of communication. Language attaches itself to geography, race, and class.

It’s the last of these that I want to focus on, specifically on Huck’s drunken, abusive father. It’s easy to see Twain as a champion of the lower class. He not only uses dialect, but he allows Huck to the be narrator of his own story, elevating him and his unique speaking style to that of the novel’s typically bourgeois subject who for so long nearly monopolized literary attention. It’s this populism that has lead to his canonization as a particularly American author.

But when we look at Huck’s father, Pap Finn, it’s clear that he’s burde ned with many of the same stereotypes associated with the poor in America. He’s lazy, he’s a drunk, and he’s an unrepentant racist. In White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, Nancy Isenberg traces common stereotypes of poor whites from early colonization to the 21st century. She finds not only that America has always had some form of class system, but also it was commonly believed that that a permanent underclass was natural and right. Pap seems to reflect America’s belief that poverty is the result of individual failings.

ned with many of the same stereotypes associated with the poor in America. He’s lazy, he’s a drunk, and he’s an unrepentant racist. In White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, Nancy Isenberg traces common stereotypes of poor whites from early colonization to the 21st century. She finds not only that America has always had some form of class system, but also it was commonly believed that that a permanent underclass was natural and right. Pap seems to reflect America’s belief that poverty is the result of individual failings.

There’s one striking passage where Pap expresses class and racial resentment against a well-educated black man who had the audacity to live in Missouri as a free man. What’s worse, the useless government didn’t even bother to enslave him:

“There was a free nigger there, from Ohio; a mulatter, most as white as a white man. He had the whitest shirt on you ever see, too, and the shiniest hat; and there ain’t a man in that town that’s got as fine clothes as what he had; and he had a gold watch and chain, and a silver-headed cane–the awfulest old gray-headed nabob in the State. And what do you think they said he was a p’fessor in a college, and could talk all kinds of languages, and knowed everything. And that ain’t the wust. They said he could vote, when he was at home…I says to the people, why ain’t this nigger put up at auction and sold?…Why they said he couldn’t be sold till he’d been in the State six months…They call that a govment that can’t sell a free nigger till he’s been in the State six months.” (36-7)

So many of the negative perceptions of poor whites that we associate with Trump voters are found in Pap. He’s resentful and embittered, and these feelings are directed towards blacks who he sees as his natural inferiors. This passage reminded me of a remark made by J.D. Vance in Hillbilly Elegy claiming that many poor whites look at Barack Obama, see a successful black man with an established family, and feel angry and ashamed.

As mentioned in White Trash, there’s a long history of elevating African-Americans by comparing them favorably to poor whites. Isenberg point to the famous photograph of Elizabeth Eckford, one of nine girls who were selected to attend the newly desegregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. In the photograph, we can see Eckford calmly walking to school while a white classmate, Hazel Bryan, shouts at her from behind. The image is powerful. As Isenberg puts it, attempting to maintain her tenuous social and economic position above blacks Bryan became the face of white trash for most of America. There’s certainly truth in this reading, and it’s long underpinned our understanding of why poor whites would fight so aggressively for slavery during the Civil War when they could never hope to own slaves themselves. (Of course, there were exceptions, even back then).

Of course, focusing too intently on animosity between poor whites and blacks serves to distance middle and upper class whites from their own more genteel bigotry. We see racism as something that only the ill bred engage in.

At the same time, poor white racial animosity has long been used by the left as an explanation for why we lack the kind of class consciousness that’s found in Great Britain. Look at What’s the Matter with Kansas or the debate over whether Trump’s ability to flip the Midwest was a result of economics or racism. (Recent research has suggested that white voters were concerned about losing their status as whites, but I don’t think you can discount ways in which economic anxiety can reinforce racism).

In some ways, Pap demonstrates the tricky relationship progressives have with poor whites in the Trump era. We believe we should be sticking up for the economically marginalized while also acknowledging that racism drove many of these people (although certainly not all) to vote for an obvious huckster who represents the exact opposite of what we believe to be the best qualities of the nation.

So what do we do with Pap? It helps that he’s not the sole or even the most prominent representation of poor whites in the novel. That position, of course, belongs to Huck himself who purposefully flees bourgeois respectability. Perhaps it’s easier to handle the stereotypes embodied by Pap because he does not fully stand for poor whites, and Twain valorizes the dusty street urchin that headlines the novel.

There’s also an opening to read Pap as more than a simple stereotype. In one exchange with Huck, he tries to steer his son away from education. First, he asks his son to read in order to see if his son even knows how, and when he sees that Huck can read, he accuses him of putting on airs:

“It’s so. You can do it. I had my doubts when you told me. Now looky here’ you stop that putting on frills. I won’t have it. I’ll lay for you, my smarty; and if I catch you about that school I’ll tan you good. First you know you’ll get religion, too. I never see such a son.” (29)

There are different ways to interpret his fear of education. Certainly, he’s afraid of his social standing in relation to his son. For his son to be educated would mean an inversion of father/son norms as he understands them. There’s also a suggestion that Pap sees education as unmanly and unsuitable for a son of his. (At one point he calls Huck a “dandy.”). But I wonder if we can’t also read some genuine attachment.

Pap could be afraid of how education might transform Huck’s speech, driving a wedge between him and his son. Twain foregrounds language’s ability to divide, so it makes sense that this form of logophobia is on the mind of Finn the elder. As Huck’s language changes, he becomes a part of the bourgeois, and it’s interesting to note that Pap links education with religion here. In English departments we so often find common allies with characters who reject bourgeois norms, but Pap seems to test these limits. Still, we might see his tirade not simply born out of personal grievances or fear of losing what little socio-economic privileges he has, but rather developed out of a fear of losing his only son. We might consider whether such a monstrous character might also have room for affection within.

In 2007, Jon Clinch published a book, Finn, that follows Pap Finn prior to the events of Huckleberry Finn. Instead of humanizing and rounding out the character, though, he makes him even more gruesome and beyond our sympathy. I haven’t read Clinch’s book, but it is interesting to note that when so many retellings try to humanize the villain (see: Wicked and Maleficent), Pap is denied a similarly new perspective.

Pap Finn reminds us that liberals and the left have always struggled when it comes to poor whites. Often they are seen as enemies while also being the kind of marginalized group we should be working to help. But people can be complicated. A racist can also be economically disenfranchised; a poor white can also benefit from white privilege. As Huckleberry Finn still teaches us, race and class wrestle with each other in troubling ways.